I was 15 years old, watching my mother and older cousin cook. Our home in this affluent Maryland suburb was filled with family who migrated to the North like my mother had as a baby, nothing compared to the large clan my mother left behind in Alabama as a young child. I struggle to remember all those faces. But even now, after being estranged from her for nearly seven years, I’ll never forget my mother’s face. I look at it every day when I look in the mirror, with a shameful, vestigial longing.

Back in Maryland, my mother and cousin spent all day slicing okra and collard greens. They fried catfish in cornmeal. My mother made a gumbo filled with spicy sausages, tomatoes, peppers and seafood, with rice. This was the food we ate when our family gathered. Gospel music playing in the background, hummed by aunties, would travel throughout the length of my body, always stopping in my heart.

When I was 13 years old, my now divorced parents separated for a while. My mother left Washington State, where we lived at the time and moved us to Camden, Alabama, for about seven months. Besides the marital tension, we also went to comfort my now deceased great aunt Hattie B.—someone shot and killed her son after he won a bet. She needed company and someone to wake up and make sure she was fed everyday. This was holy work.

Unsurprisingly, what I remember most about Camden is the food. There is nothing in Camden to do but eat. We ate by my mother’s and cousins’ hands, ingredients bought at the Piggly Wiggly where I wrinkled my nose at the chicken feet, but my mother got excited because she hadn’t had them in years. Going to Walmart was a small road trip. For fun, my cousins and I would walk to Bones—a gas station that sold fried chicken and sunflower seeds that we’d suck the salt off of and spit back into the dirt on our way home. Camden is more of a village than a town. But it has a long history.

My maternal grandmother used to tell me how, in the 60s, Camden was a place civil rights workers used to come to advocate for our right to vote. They gathered at my family’s church, Antioch Baptist, where the Klan used to shoot while the freedom fighters hid under the pews. My grandmother—a former sharecropper—told me of Camden’s poverty, hunger, degradation, sexual violence and lynchings. Two of my relatives are interred in the Lynching Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama—constant reminders of what was done to us. I wasn’t expecting to see the jar of dirt representing the place where my family member was killed; when I did, I broke down into sobs.

I’m estranged from my maternal grandmother now, too. I blame her cruelty towards my mother for my mother’s cruelty towards me, inherited trauma that I feel will never end unless I sever these connections. But I hold onto some things—always the memories of food.

Unlike my mother who learned to cook from my paternal grandmother, my maternal grandmother was an atrocious cook. So she fed us stories about food. She told us about her brothers who hunted venison and rabbit, because meat at the grocery store was expensive. She told us how, on Christmas, her parents got them oranges for presents, because fruit was also hard for sharecroppers to come by. She told us how her mother would scrape together cornmeal and okra and whatever else she could find to make a meal. Those stories are all I have now to remember my family, this half of my heritage.

My father’s family is a more privileged Creole Caribbean family that migrated to America before my mother’s family migrated to the North, with less horror in their past. On this side, a recipe or a meal is just a phone call away. My stepgrandfather randomly asks us if we want crabs, and he steams them alive with plenty of Old Bay. With tables covered in the Washington Post, we eat the meat with melted butter. And my father’s mother, my grandmother, makes me curry or brown stew chicken every time I come home to D.C. Sometimes, her brothers slip up and refer to her as my mother. It’s been so long since my real mother was in the picture.

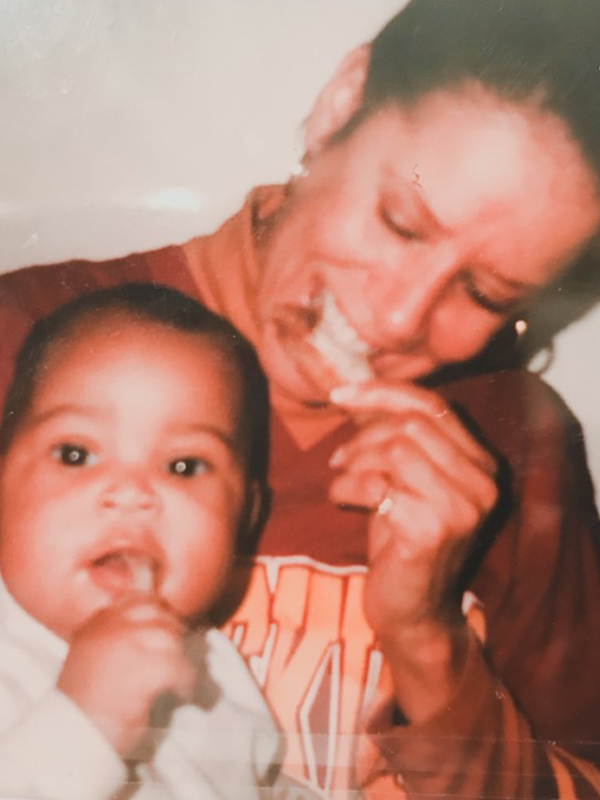

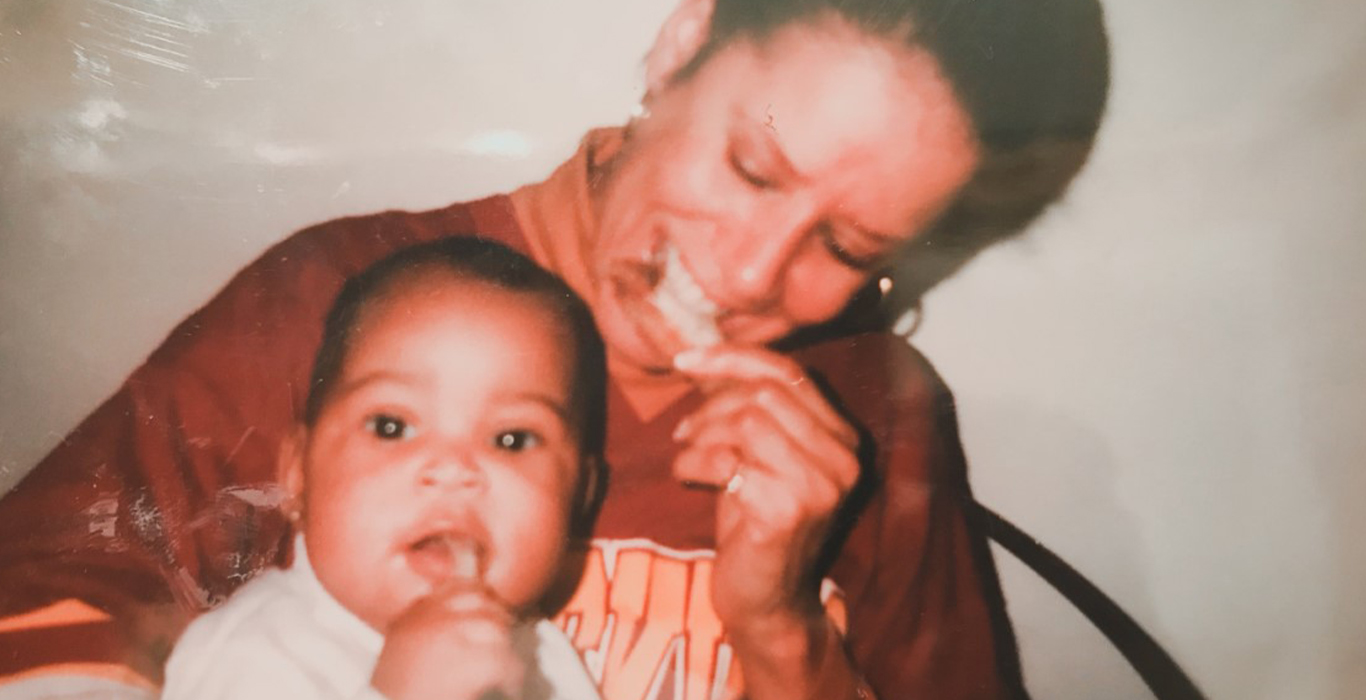

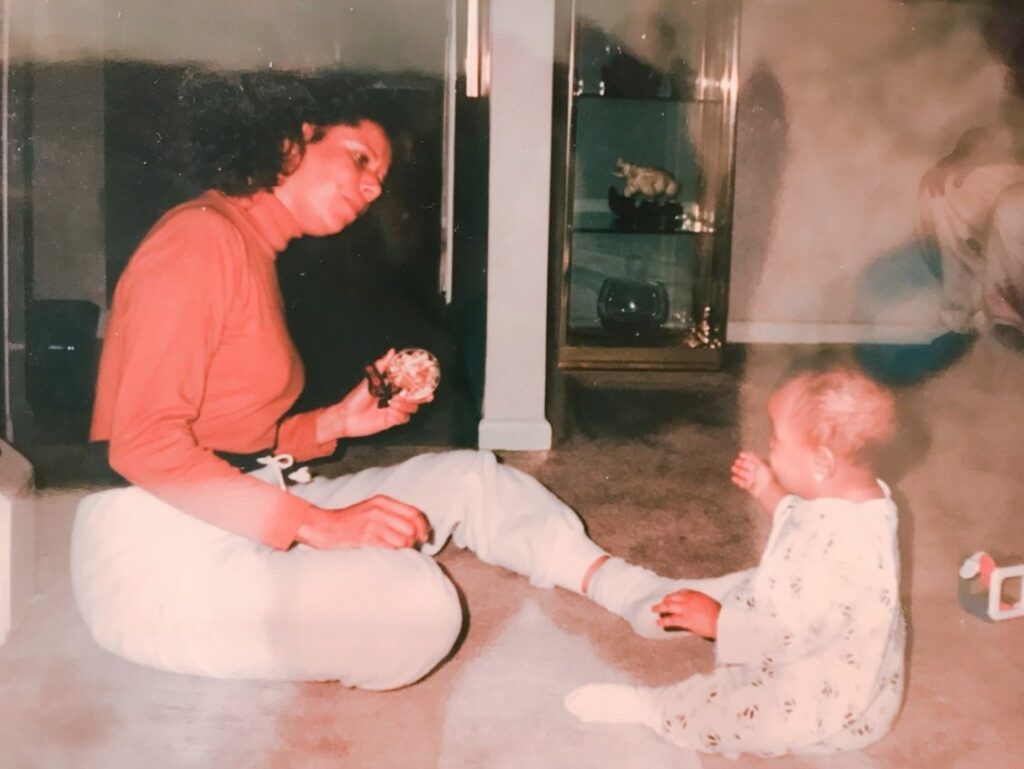

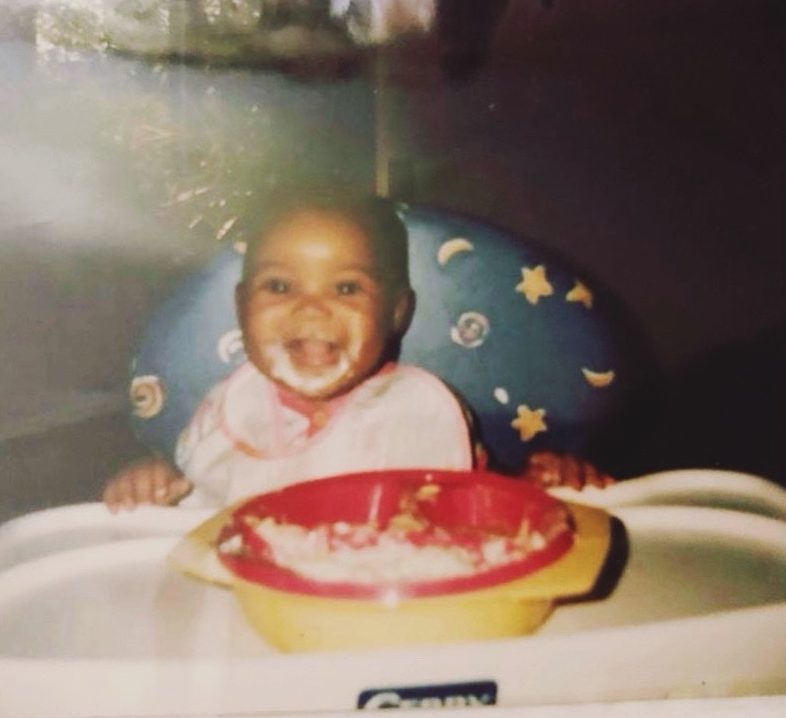

My mother refused to give me my baby pictures—she has most of them—but my paternal grandmother loves to bring out photos of me eating as a baby. I know how to reach my hands in hot plantain oil. My father can remember putting scotch bonnet sauce and Tabasco on my tongue, a Caribbean tradition of adjusting children to the spice in our food. I remember my nanny insisting I eat the eyes of the snapper because they were the best parts. I gagged when she popped them whole into her mouth.

But on my mom’s side, food traditions remain elusive. I don’t know how my maternal great-grandmother made venison or rabbit. I have no one to ask. I don’t know how my cousin achieved that crispy cornmeal on her okra. I don’t know how to make gumbo the way my mother made it or biscuit dough the way my aunt made it. Sometimes, trying to recreate them feels like an act of forgery. Am I still a daughter of Camden when I no longer have a Camden mother?

I have often thought of the experience of Black Southerners who left during the Great Migration as similar to the experience of immigrants, although our border is hazier. It is a diaspora within a diaspora within a nation that never stopped being divided. Within our families, there is so much loss. That’s why we’ve always held on, why we’ve always made the pilgrimage to family reunions every few years.

Perhaps I am selfish for throwing this away, for not calling to ask about those recipes. But I have to remind myself that, to save my own life, I removed myself from the hands that both cooked for me and hurt me. I also have to remind myself that this history makes me half of who I am.

And in moments of distress, I think of the road that leads to Camden. It’s pitch black in my memory, the stench of a nearby paper factory wafting through my nose. I remember the drive down there from D.C. or Seattle, the radio changing from R&B to Country to nothing but static. I know without asking that my mother thinks of that road all the time, too. Sometimes I get the overwhelming urge to call her, and I know I should not.

So, instead of calling, I reach for a heavy-bottomed pot to make gumbo and think of those trips to Mobile. I throw in ingredients from my father’s family: crab meat, scotch bonnet and a dash of Jamaican Pickapeppa sauce. To remember my mother, I slice the okra and find the sausage closest to the one we ate in Camden. I use duck because it’s the closest thing I can find to rabbit.

When I cook, I am reconstructing memory and hoping to reconstruct broken bonds I know may never heal. But the gumbo pot has room for all that we have lost, all we have gained and all that is yet to come.

RECIPE:

Gumbo

INGREDIENTS

THE DUCK CONFIT

6 duck leg and thigh pieces, skin on

3 bay leaves, crumbled

1/2 tbsp kosher salt

1/2 tbsp ground allspice

THE GUMBO

5 tbsp duck fat from the confit—if you didn’t get enough, add olive oil or vegetable oil for the rest

1 sweet onion, diced

1 red pepper, diced

1 green pepper, diced

2 stalks of celery, diced

8 cloves of garlic, minced

4 tbsp all-purpose flour

1 1/2 tbsp tablespoons tomato paste

1 tsp Black pepper

2 tsp ground allspice

1/2 tbsp curry powder

2 tbsp Pikapeppa Sauce

Salt and pepper

6 bay leaves

5 Roma tomatoes, diced

3 scotch bonnet peppers, diced. Remove the seeds if you have a moderate spice tolerance.

10 oz andouille sausage (I use chicken but you can pork if that’s your preference) sliced diagonally in 1/2 thick slices

7 cups chicken broth

4 cups okra

Fresh thyme

1/2 lb medium shrimp, shelled and deveined

5 oz claw crab meat

4 oz smoked tinned oysters or fresh if you prefer

1 cup chopped scallion, for serving

Steamed basmati rice (you can use any white rice on hand)

INSTRUCTIONS

1. For the Duck Confit: In a small bowl, combine the bay leaves, kosher salt, allspice and black pepper. Rub the mixture onto the duck and place into a pan. Cover tightly with plastic wrap and refrigerate for 24 hours, or overnight.

2. When the duck has finished brining, preheat your oven to 325 degrees and place a cast-iron pan in the oven. When the oven and pan have finished pre-heating, remove the pan and place the duck legs in the pan, skin side down. Cook the duck legs over medium-high heat until the fat has begun to render and the pan is covered in about 1/2 inch of fat. Flip the duck legs, this time skin up, cover the pan with foil and place it in the oven.

3. When the duck has finished brining, preheat your oven to 325 degrees and place a cast-iron pan in the oven. When the oven and pan have finished pre-heating, remove the pan and place the duck legs in the pan, skin side down. Cook the duck legs over medium-high heat until the fat has begun to render and the pan is covered in about 1/2 inch of fat. Flip the duck legs, this time skin up, cover the pan with foil and place it in the oven.

4. Roast the duck legs for 2 hours, then remove the foil and roast for 1 hour, until the skin is crispy and the duck is golden brown. Remove the skin and reserve the duck fat for your gumbo. Shred the duck meat. Freeze skin and bones to make a broth later.

5. For the Gumbo: Heat a 6-quart Dutch oven or heavy-bottomed pan. Add your duck fat (and olive oil if you didn’t get enough duck fat.)

6. Add in celery, onion, red pepper and green pepper. Sauté, stirring frequently, until the vegetables are slightly browned and soft.

7. Add in flour, one tablespoon at a time, making sure to scrape up all the brown bits on the bottom of the pan before you add the next tablespoon. Take care not to burn the flour at the bottom of the pan. If it starts to burn, take off the heat and scrape vigorously, discarding any blackened bits.

8. Add in tomato paste, garlic, paprika, cayenne and curry powder. Cook and stir for 1 minute, still taking care not to burn the flour at the bottom of the pan. Add in diced tomato, sausage and scotch bonnet pepper, cooking for 3 minutes. Season with 1 teaspoon salt.

9. Add in chicken broth and continue to scrape brown bits. Simmer, covered, for 30 minutes until the mixture has thickened from the consistency of a soup to more of a stew. Add salt or other spices to taste.