A 1948 quote from the late Ebony magazine food editor Freda DeKnight brought Nicole Taylor to tears when she read it while recently promoting her new Juneteenth-inspired cookbook Watermelon and Red Birds: A Cookbook for Juneteenth and Black Celebrations.

DeKnight, in her book A Date with a Dish, had written: “It is a fallacy, long disproved, that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads. Like Americans living in various sections of the country, they have naturally shown a desire to become versatile in the preparations of any dish, whether it is Spanish, Italian, French, Balinese, or East Indian in origin.”

Those words were published almost 75 years ago, yet DeKnight had perfectly encapsulated Taylor’s own present-day belief in boundless Black culinary curiosity and experimentation.

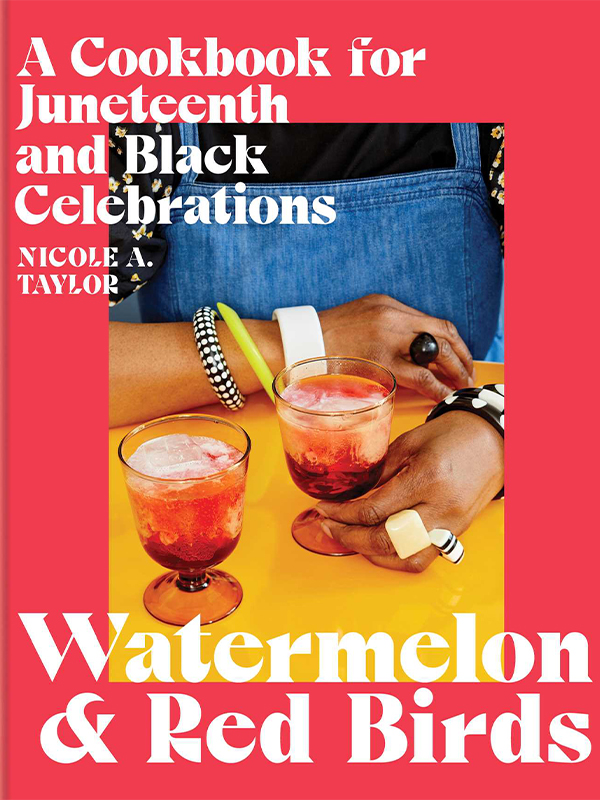

This shared theory forms the foundation of Taylor’s Watermelon and Red Birds, which was released this week.

“It’s literally 1948 to 2022, yet we were on the same page,” Taylor, who often reflects about DeKnight’s legacy, tells Sweet July. I hope [the spirit of African-American culinary exploration] comes across in the book.”

Watermelon and Red Birds is an unabashedly modern take on Black American food traditions. It draws on Juneteenth, the observance that marks when Black residents of Galveston, Texas, got word of freedom on June 19, 1865—more than two years after the Emancipation Proclamation liberated enslaved people in the rebelling South. It became a federal holiday last year.

Long-awaited freedom merited celebration, and Texans began remembering that day with community gatherings featuring red drinks (perhaps to symbolize the blood shed in slavery or in the tradition of West African drinks flavored by crimson-colored kola nuts or hibiscus), barbecue, ice cream and other sweet treats.

Taylor’s book is organized to generally follow those Juneteenth mainstays, starting with spice blends fit for a fish fry and ending with updates on classic desserts. Collard greens, sweet potatoes and staples of the Black Southern pantry are present. But her spin flips culinary convention; the cookbook includes the tang of fig-vinegar barbecue sauce and dukkah seasoning; “Southern-ish” potato salad, meatless baked beans and veggie-rich salads; a sweet potato spritz; zucchini corn dogs and beef ribs with harissa; hibiscus-Sichuan snow cones and a “liberation sundae” with dairy-free chocolate sorbet and rhubarb compote.

The radish pound cake will sneak up on you, says Taylor. “Everybody can identify with pound cake,” she adds. “I’d take my pound cake to a party as a showstopper. People don’t know what to think about it. But when I tested it over the last year, people really, really liked it. Even my mom said it was good.”

This is grown folk food for the intrepid cook, with more than enough for the kids to partake. That’s in the spirit of both Taylor’s own upbringing and Juneteenth celebrations over time, from the big segregated fairs of the early 20th century to today’s family cookouts. Taylor didn’t grow up in a household where cookbooks were common, reading instead the recipes in magazines like Jet. For this project, she became relentlessly focused on writing not just a cookbook but curating Black joy and community through food.

“I can say joy as many times as I want because we need to affirm it.”

“The word ‘joy’ is all throughout my book, and I was just kind of like, ‘Ooh, am I saying ‘joy’ again?’” says Taylor. “Then I was like, whatever. I can say joy as many times as I want because we need to affirm it. I also am very [aware] that my mama ain’t using the term #BlackJoy, but she knows it. I know that when my mom would get her check and she had extra money (because she worked overtime), she went to the fish market to buy a bunch of fish, to cook for her friends on the weekend. That was her saying, ‘I love you. And I know we had a long week, but let’s celebrate. Let’s pop that top on our beer can, and let’s lean into Black joy.’”

As a cookbook, Watermelon and Red Birds can be read—and used—as a straightforward guide to planning a party menu or cooking single dishes like apricot lamb chops over fire. It comes with sections that break down basic details for home cook. In one such section, Taylor lists and describes the inexpensive but indispensable gadgets she keeps by her side. She explains that melon ballers can bring decorative, three-dimensional flair to a cheese plate and why seafood baskets are a must-have for grilling.

Or, Watermelon and Red Birds can be read as a quietly subversive, yet imminently political text. It declares that the Black home cook has aspirations beyond soul food without denigrating it, that Black Southerners who sprinkle their cantaloupe with salt or pepper could also enjoy a salad of melon and feta.

“I chose in this book to center the goodness of watermelon and the happy memories that I know so many Americans and particularly Black Americans have around the fruit.”

Taylor also refuses to give much room to the harmful, racist stereotypes of watermelon. Instead, she recalls walking into Bell’s grocery store in her hometown of Athens, Georgia, in summertime, picking a big watermelon out the cardboard box and watching it roll around on the car ride home. Her family would cut wedges and send her outside with newspaper to catch the juice that would inevitably drip on inside floors.

“It’s not lost on me that even though watermelon is a classic, all-American summertime fruit, for many Black Americans, it brings a lot of pain,” says Taylor. “And some of that pain is due to the very gross and disgusting advertisements that were put out by so many American and foreign companies. So I chose in this book to center the goodness of watermelon and the happy memories that I know so many Americans, and particularly Black Americans, have around the fruit.”

Taylor’s culinary journey began as a student at Clark Atlanta University. “There was a brand-spanking-new dorm, suite-style apartments with a kitchenette,” she says. “I was cooking college food: burgers, a lot of starches, few vegetables. But you couldn’t tell me nothing! That place is where I really learned how to host. I learned how to make people happy through food and drink, through music, through creating an atmosphere that was electric. When I look back, that was the start of me entertaining and leaning into celebration. Always.”

Since then, Taylor has centered her brand on writing about various forms of celebration, such as homecomings at historically Black colleges and universities. In 2011, she started going to Juneteenth celebrations in Brooklyn, where she lives when she’s not in Georgia.

“We have had this weird world of sorrow and, at the same time, we can eat, laugh, sing and dance. I wanted to show this is who we are.”

When Taylor’s agent began suggesting that she consider doing a Juneteenth cookbook, she brushed it off. She had set her sights on writing a brunch cookbook and thought a Juneteenth book would be a hard sell. But the murder of George Floyd and the countless other killings of Black Americans by law enforcement made her take the idea more seriously.

“The summer of 2020 solidified for me that Black people needed joy,” says Taylor. “We needed something to drown out all the sorrow and sadness. For so long, for Black people, we have had this weird world of sorrow and, at the same time, we can eat, laugh, sing and dance. I wanted to show this is who we are. We are a group of people who, no matter what, we gonna celebrate, we gonna fry fish and shrimp. We’re gonna have our red drink, and we’re gonna have a barbecue. And we are gonna play ‘Before I Let Go’ at the cookout.”