Black women are leading the art world’s renaissance (and don’t just take our word for it). Even amid bleak inequities in the industry—Black women artists held a 0.5 percent share of museum acquisitions and 0.1 percent of auction sales between 2008 and mid-2022—this group of trailblazers continues to forge more equitable paths forward.

Case in point: Lindsay Adams, a Chicago-based artist and writer living with cerebral palsy, who brings an anthropological approach to her art practice. “My career is very much developing,” says Adams, but the full-time MFA student exemplifies a more promising future for the art world. Her work [Down At The Cross, 2022, oil on canvas] has been acquired by the Baltimore Museum of Art, and, most recently, The Black Art Experience and Soho House Chicago hosted Adams as a panelist for a discussion titled Revitalizing Black Art: Navigating Institutional Relationships and Building Creative Communities.

Here’s what Adams had to say about how she and others are implementing necessary change in the fine arts.

What’s your mission statement?

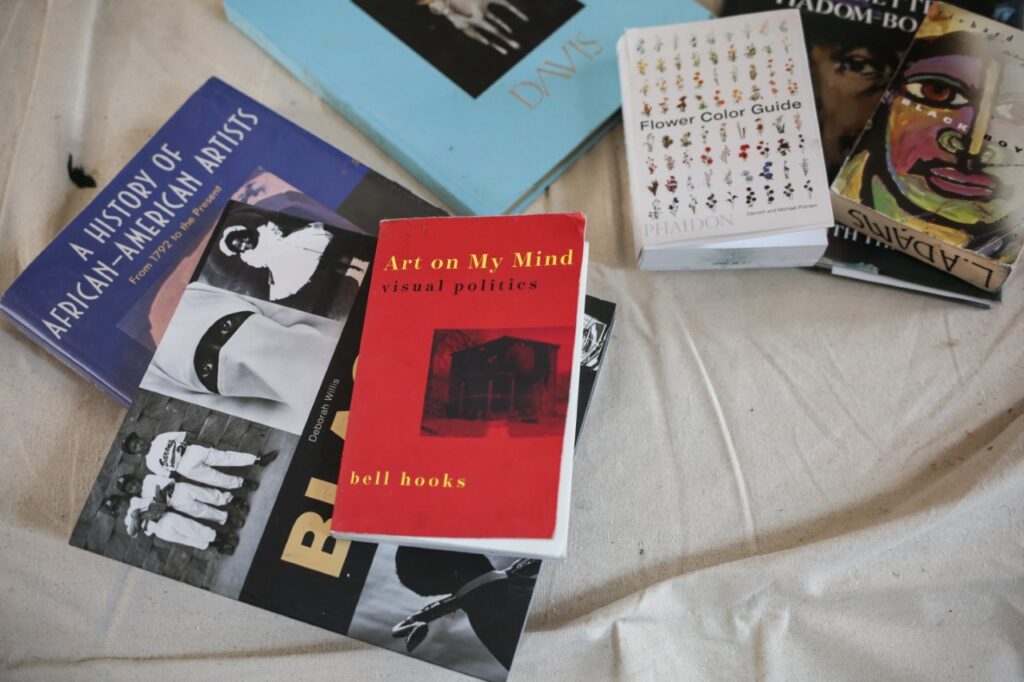

Lindsay Adams: In my practice [as a painter], I’ve been having a dialogue about memory and location. I’ve been using [my floral works] to interrogate and express nuance regarding the Black ancestral connection to land—what that feels like in terms of memory and lived experience—while also leaving space for imagination. I’ve been thinking a lot about what land represents in terms of identity and the anthropological Black experience. In my figures, I most often situate a solitary female. With my flowers, I create spaces as a testament to what we can do, what freedom looks like and what nuanced personhood looks like.

From your perspective, what conditions have caused Black women artists to be underrepresented?

LA: It’s access to information. Systemically, this space has not favored the careers of women artists; the institution and the system weren’t made with us in mind. We all know there are a million amazing women artists; it’s just that we are not on the system’s radar. That’s part of the bigger dilemma about womanhood and what it’s like to exist in these spaces. [There are] other layers of work that we have to do just to get through the front door.

That said, it’s important to note that I’ve had a [non-linear] path in the fine arts. All of the choices and artistic endeavors I made were part of the journey for me to find my visual language. My academic background [in foreign relations, sociology and cultural anthropology] informs my art practice in many ways. I took a roundabout way to find myself here; it wasn’t a straight line. I’m happy about that because it gives me a unique perspective.

What practical steps can be taken to close the art industry’s opportunity gap?

LA: I think one step is [considering] who is making decisions. [Another step would be] hiring more Black curators, Black writers and Black thought leaders— to be in dialogue [with power]. It’s important to have people in places that have a say and decide how we move forward.

Why is mentorship important to implementing change?

LA: Being an artist is a very challenging thing; there’s the critiquing of your work, knowing what opportunities to apply for, making sure you’re around like-minded individuals, making sure you’re reading and listening. Of course, you have your trusted advisors. It’s been very important for me to be able to pick up the phone or send a text and ask, “What do you think about this opportunity?”

It’s important to be authentic and to do everything with intention and integrity because you never know who is bringing up your name, or where they’re bringing it up. Having those authentic, non-transactional relationships, I think, is very important. I’m so grateful for the people who have connected me to others who I’m inspired by and give me great feedback—even in unofficial mentorship relationships.

What advice would you give young women who aspire to follow in your professional footsteps?

LA: If you have a natural talent—a God-given gift—then it’s like, “Okay, I want to do this. I want this to be the ministry I share with the world.” You need to maintain that integrity and vulnerability because if you don’t, the work will suffer. When you want to be a professional artist, identify the technical steps that you need to take to get there. I swear by art lectures—in person, online, on YouTube. I’m listening to people who’ve had to break through ceilings, who have messed up and had to fix it. I have this longing to learn and understand the nuances of things. I’m consistently seeking to learn, [and] haven’t even touched the surface yet of what I plan to do.

I’d say make what you want to make and push it as far as you want to push it as far as making art. Learn as much as you can learn [about what] suits you in your practice.

[Being an artist] is a lonely path; the studio is a lonely place. But when you have a body of work that you’re happy with, lean into that when it gets hard. Lean into your love for making [art] and learning when the day-to-day gets hard. Take a step back when you need to, and then get back to it.

What excites you the most about what’s next in the industry?

LA: There are people trying to push the needle forward and creating [more equitable] spaces that we can occupy. It’s my intent to take up space. I’m going to take up all the space that I need to. I’m inspired because I see that there are other people doing the same thing: creating spaces for us to have a place, and for us to be able to say what we want to say.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Featured image: “Down At The Cross” (2022); photographed by Hana Tajima.