When Reem Assil opened Reem’s California, her Bay Area-based Arab street corner bakery, she set out to do three things: narrate her own story as a member of the Palestinian Diaspora in California, integrate her social justice work with food, and embody the essence of Arab hospitality inherited from her Palestinian-Syrian family.

“I’m also an Oakland girl,” Assil tells Sweet July. “All these intersections of community are at the crossroads of Reem’s. My gift to the world is this experience of Arab hospitality and the resilience of Palestinian identity.”

The recent tragedies in Palestine have been indescribably painful for Assil. Since early October, over 30,000 Palestinians have been killed in Gaza by Israeli forces, with what human rights experts have estimated to be the equivalent of at least two nuclear bombs. “We’ve lost at least 40 members of my family,” she says quietly.

Originally from Northern Gaza, Assil’s family has witnessed the devastation caused by bombings, abject starvation, kidnappings and executions, and a near-total communications blackout. “My family came from one of the most beautiful neighborhoods in Northern Gaza, the Rimal neighborhood,” she explains. “They have since fled; now my family is scattered everywhere.”

Many across the world are seeing the horror of the occupation of Palestine for the first time. But for Palestinians like Assil, this reality is one they were born into—a reality shaping both their fondest memories and deepest pains.

“I went to Gaza once in 1994, and that was a pivotal moment in my understanding of my own identity,” Assil says. She was 11 years old, and Israeli forces were dismantling settlements in the Gaza Strip after destroying all the infrastructure. Assil admits that as a “suburban kid with privilege,” seeing the economic despair and military aggression in Gaza was confusing to her. However, she also recalls beautiful moments of hospitality, and the power it has to bring love, healing, and strength in the face of adversity.

“My family had to drive hours just to buy water from the Israelis to make sure we had enough for bathing, coffee, and cooking. They were horrible circumstances, but going to get the water was an act of hospitality, as was going out of their way to find the ingredients to cook these amazing meals for us,” Assil says of the visit. “They created a feeling of abundance and hospitality, even in the midst of devastation.”

One dish that exemplifies this spirit for Assil is the iconic maqluba, meaning “upside-down” in Arabic. It’s a one-pot rice dish with regional varieties—in Gaza, they use lamb and eggplant; in the West Bank, it’s chicken and potatoes, Assil says—that gets flipped over onto a tray when it’s done, making what she calls a sort of “rice tower.”

To Assil, the maqluba is a communal dish that “unifies Palestinians all over the world,” from the West Bank to Gaza, to the region referred to as modern-day Israel, to the diaspora around the globe. Her own adaptation incorporates fresh, seasonal California produce, blending Palestinian heritage with local flavors. “It looks different from village to village, from family to family, but it’s the thing that unifies us,” she says. “It’s quintessentially Palestinian.”

Another cherished delicacy from Assil’s childhood is musakhan, Palestine’s national dish, which celebrates the olive oil harvest. It consists of roasted sumac confit chicken and caramelized onions. It’s usually served in a traditional bread called taboon, but growing up in California, Assil’s mom wrapped the ingredients into a tortilla, cementing her “Pali-Cali” take on musakhan. At Reem’s restaurants, the musakhan tortilla wrap is also served with local arugula and pomegranate seeds. Other specialities include shakshuka tarts, a jammy 6-minute egg with labneh and chile morita crunch, and the traditional Fatayer Sabanikh, a spinach, onion, and sumac hand-pie.

“People ask, ‘Is your food Californian, or is it Palestinian, or is it Lebanese, or Syrian?’ It’s all of those things, not one or the other,” Assil says.

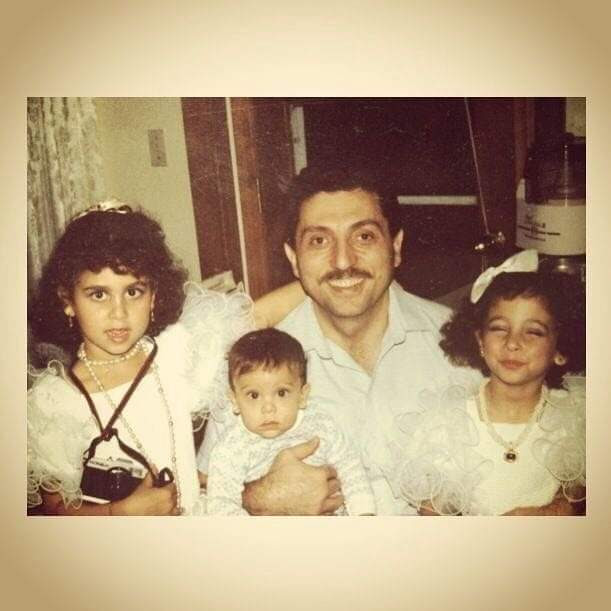

Through her food, she tells the story of her family’s journey, from their displacement to their resettlement in California. Assil’s grandmother became the first refugee in their family in 1948, during the Nakba (“the Catastrophe”), when the Israeli state was formed and Palestinians were killed and driven from their homelands, forbidden to return. She was from Yaffa (modern-day Tel Aviv), and Assil’s grandfather came from a prominent family in Gaza, where her mother was born. In 1967, when Israel took over Gaza in the West Bank during the Naksa (“the setback”), the family was permanently expelled and sought refuge in Beirut. There, Assil’s mother met her Syrian father, and the couple eventually moved to Boston, where Assil was born. Assil settled in California at 22.

It’s an enraging story of displacement, but also one of building community along that journey. Assil asserts that nothing will ever replace Palestinians’ right of return to their homeland—a right that Israel still denies them—but that finding a place is crucial. “Sometimes people are able to create a home away from home, and sometimes they’re not at odds with one another. That’s the beauty of it.”

Assil also found beauty in baking during a 2010 trip to Lebanon and Syria with her father. “I think bread is the lifeline of Arab people,” she says. As they visited street corner bakeries, Assil realized what she wanted to create. “That feeling of the communal oven, of community, of connection. There was a lot of political turmoil there, but you wouldn’t feel it when you were inside those bakery doors.”

So often, attempts to use food as a tool against oppression can lack real impact. The result is rather toothless; a statement that doesn’t say anything. Well-meaning words about unity and humanity are great, but without a clear call to action, people can enjoy a cultural experience without feeling compelled to support the people behind it. As Assil recently told Mondoweiss, “We don’t want to get to a place where it’s okay or cool to say a food is Palestinian, but no one is calling for a ceasefire or the end to occupation.”

“It bothers me a little when [people in the food industry] say ‘food brings people together’ and the story ends there,” Assil says. “That’s not what my food is about. My food is an invitation to build deeper, to build understanding. I’ve heard the term ‘discomfort food,’ and that means we’re not there to just feed people and make them happy—we want to raise their consciousness and leave wanting to do something about it.”

She adds, “policy follows culture,” a reminder that the power of food isn’t just in sharing meals, but in shaping policies that bring justice to the people. By using food to express political commitments, we can transform communities and even relationships within our own families.

Bearing witness to this a genocide means seeing three generations of her family—her mother, herself, and her young son, Zain—process it together. “I’m watching my mom go through stuff she’s suppressed for a long time after being displaced in 1967,” says Assil. “The lessons of our struggle remain with us, but hopefully the trauma gets healed as we move closer to liberation.” She says that her son, who she takes to protests and teaches about his heritage, often imagines a free Palestine. While Assil doesn’t sugarcoat the realities of the injustices they face, she creates a space for him to dream up a new world, one of peace and life.

“He asks me, ‘Mama, are you dreaming of Gaza? When we rebuild it, will there be trees?’ And I tell him that yes, the Gaza we are going to rebuild is going to be even more beautiful because it’ll be in a free Palestine.”

As a refugee, Assil’s mother has found healing in her grandson’s unwavering belief in a free Palestine. This hope contrasts with Assil’s own childhood doubts; she never imagined Palestine would be liberated, and questioned why the struggling continued.

“My uncle said, “We fight so you remember you’re Palestinian and your children will remember that they’re Palestinian. Palestine is not just a physical place. It’s a people.’”

In honoring her family’s legacy and Palestinian identity, Assil embodies resilience, hospitality, and tireless commitment to social justice. Through Reem’s restaurants, she not only preserves Palestinian culinary traditions but also amplifies the voices of her community, ensuring that their stories are heard and their struggles acknowledged on a global stage.

This feature is part of The Village Issue. Read more about the gamut of our most cherished relationships here.