The steam from tender goat soup (maraq ari) on the outskirts of Mogadishu; the feeling of fingers folding salmon sambuus in a Seattle home; laughter at an intimate group dinner in L.A. These all have one thing in common: they are the memories food writer and chef Ifrah Ahmed calls upon when creating recipes for her sought-after food pop-ups, MILK & MYRRH, which she started in 2019.

For Ahmed, whose family resettled in the Seattle area in 1996 after the Somali Civil War, these traveling culinary experiences are informed by her surroundings in the Pacific Northwest and her Somali culture. The name MILK & MYRRH is inspired by a vintage 1960s Somali cookbook Ahmed stumbled upon when she was looking for a name for her pop-ups.

“Within the cookbook, there was this line that said Somalia had many names, and one of them was the land of milk and myrrh,” the accomplished recipe developer, with bylines in the New York Times, Washington Post, LA Times, and Whetstone Magazine, tells Sweet July. “[Frankincense and myrrh] originated in Somalia, so visually, it was very striking. It just was so beautiful, so poetic to me.”

Of her process for designing the menu for MILK & MYRRH events, Ahmed says, “I’ll think about, ‘What did I grow up eating that I really loved? How can I honor the classic way of doing things and the classic ingredients—but put my own translation on it?’”

Last year, for the LA Times, Ahmed shared her recipe for salmon sambuus—a dish that combined her Somali—sambuus are usually filled with meat and vegetables, sometimes tuna—and Pacific Northwest background. “That recipe was a collaboration,” she says. “I would ask my mom, ‘What did you put in the sambuus?’ And then I would tweak it according to my own taste or what ingredients I thought would parallel.”

Tweaking is often necessary, as re-creating family recipes to a T is nearly impossible, says Ahmed. “The difficulty is that when I’m looking at things I was inspired by in my childhood, there’s no exact measurements of anything,” she says, with a laugh. “I’ll ask, ‘What did you put into this? Or how many? Or how much?’ And my mom’s like, ‘Just do it until it feels right.’ [This] is challenging as a recipe developer, because I can’t say that to whoever’s reading my recipe [especially] if they have no knowledge of Somali food.”

Across the African Diaspora, to learn a new recipe, often one has to call their mother or grandmother and piece together snippets of instruction, pair them with visual memories and create a new muscle memory that’ll eventually be passed down to the next generation of friends and family. Somalia is no different. “Somalia is known as the nation of poets; our recipes, like our poetry and our songs, are passed down orally,” Ahmed wrote for the LA Times.

But in digital media, recipe measurements need to be exact—passed down through hyperlinks, not an aunt instructing verbally during a family holiday. This more rigid form of modern-day recipe development can be hard to marry with the natural fluidity of African Diasporic dishes. But this union isn’t impossible. Case in point: the vintage Somali cookbook Ahmed once stumbled upon—the inspiration behind her pop-up.

Even when exact measurements are necessary, Ahmed always approaches cooking the way her mom suggests: She does what feels right. For example, in Somali communities, Ahmed says there’s often a preference for chicken, goat and camel meat, but growing in the Pacific Northwest, many of Ahmed’s favorite dishes feature seafood. Last December, Ahmed hosted a MILK & MYRRH Somali seafood dinner in Seattle, featuring crab sambuus with tamarind basbaas, rockfish suqaar with canjeero, and wild salmon iyo bariis.

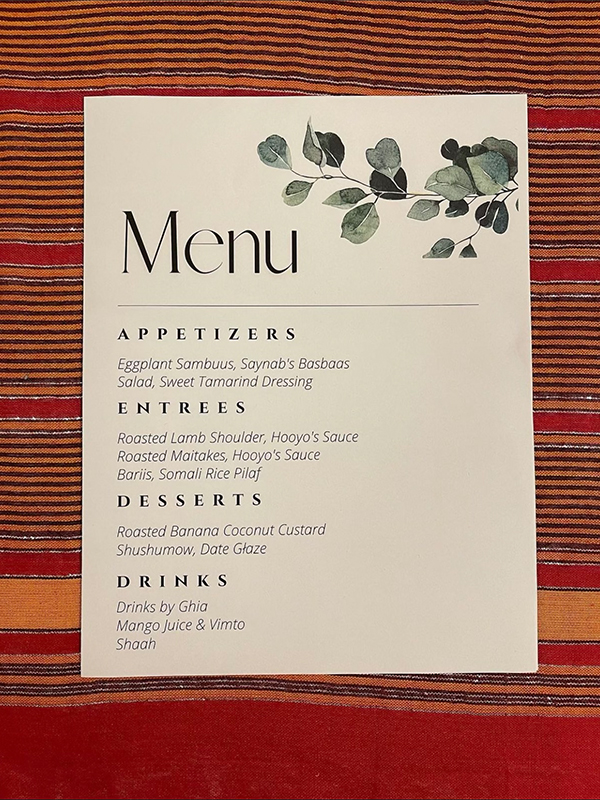

Unsurprisingly, others have taken note of Ahmed’s unique talent. This past Eid al-Adha, the holiday marking the end of Ramadan, Ahmed was invited to come to New York City and be the guest chef at an intimate iftar dinner funded by Nike for Muslim artists, writers, organizers and creatives. The organizers—Zara Rahim, Ladin Awad, Zenat Begum and Mohammed Fayaz—gave Ahmed “free reign” to design her iftar menu, which she tailored to connect with the attendees, many of whom were her friends. Many had never tried Somali cuisine before, and many had longed to attend a MILK & MYRRH pop-up but hadn’t been able to. With her friends Asha and Hana assisting her with preparation, Ahmed helped create an unforgettable night.

“It was such a beautiful experience,” says Ahmed. “It’s not often that we get to gather with our Muslim peers in this way, in a space that prioritizes our Muslim identities but also celebrates our Black and Brown identities and our identities as artists and creatives.”

As her work continues to evolve, Ahmed finds herself inspired by food writing that talks about memory and taste, and their connection to larger issues like injustice and questions of identity and existence, like Alicia Kennedy, Eric Kim, Yewande Komolafe and Mayukh Sen.

“I also very much identify as a writer and would like to focus on storytelling more than being in a kitchen everyday,” says Ahmed—sharing that she’s been working on a cookbook as well.

Ahmed isn’t sure if she wants her own restaurant one day—MILK & MYRRH pop-ups sustain her creatively in a way that a one-off location might not. Over the past few years, pop-ups and chef residencies have taken root in the culinary world. The novelty of impermanence and innovation has extended to veteran celebrity chefs and emerging chefs alike. “I like the freedom of doing traveling pop-ups,” says Ahmed. “It speaks to my nomadic spirit.”

So for now, MILK & MYRRH’s beauty will continue to lie in its transient yet memorable way of connecting Somalis from coast to coast, and introducing people who’ve never even heard of dishes like anjeero to the intricate world of Somali cuisine.