Growing up, Kali Fajardo-Anstine’s sister Avalon had a severe phobia of snakes. “If we were watching TV and a snake came on, she would run out of the room,” Fajardo-Anstine tells Sweet July. And it wasn’t just her sister who harbored an intense, coiling fear of the reptiles. “I grew up in a house where people were terrified of snakes,” she adds.

So it was intriguing when Fajardo-Anstine discovered she had a snake charmer in her family—her great-uncle Jakie.

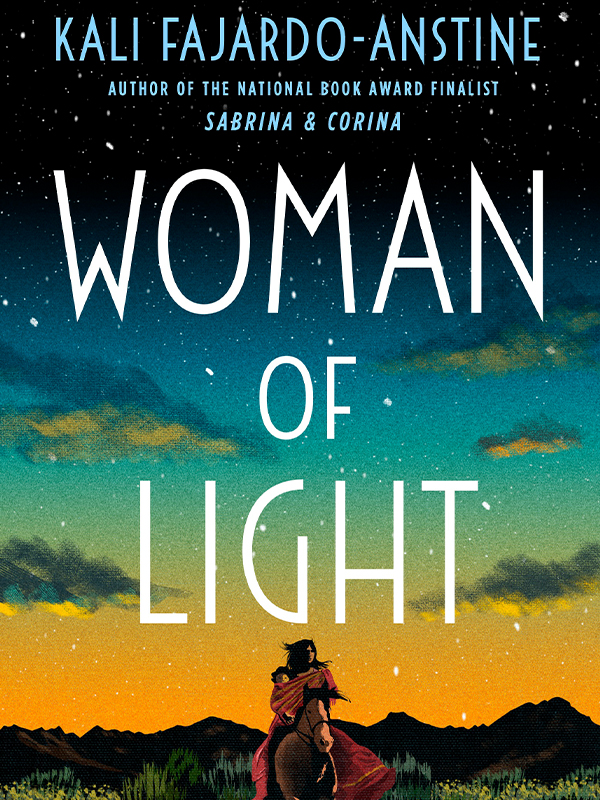

Jakie served as inspiration for Diego, one of the characters in Fajardo-Anstine’s new book, Woman of Light, which released today. Diego makes a living performing tricks at festivals with his pet snakes, “two large, aggressive rattlers” named Reina and Corporal. He’s also fiercely loving and protective of his Luz—meaning light—who is based on Fajardo-Anstine’s Auntie Lucy, Jakie’s sister in real life.

Most of the characters in Fajardo-Anstine’s second book are based on her family members and ancestors. Woman of Light is pulled from the stories Fajardo-Anstine—who also published a short story collection in 2019, Sabrina and Corina—heard growing up of her family coming north from Southern Colorado to Denver during the 1920s and 1930s. Over five generations, Woman of Light follows one family’s journey of love, displacement, survival and community.

This real history is what makes the cast of characters in the book impossible to forget. While Luz is the book’s protagonist, readers of this family epic will also find themselves charmed by secondary characters like Luz’s bubbly cousin Lizette, her loving and protective Aunt Maria Josie, the Sleepy Prophet Desiderya and the sharpshooter Simodecea.

Fajardo-Anstine says her Auntie Lucy was a wonderful storyteller, which helped her write every character in Woman of Light so vividly. Even the rattlesnakes. Luckily, her snake-fearing sister, Avalon, was surprised to discover she enjoyed the pet snakes Reina and Corporal as characters and didn’t feel afraid when she was reading about them in the book. “They slept in his bed; They’re his companions,” says Fajardo-Anstine. “Maybe that’s why reading about Reina and Corporal isn’t so hard [for people with snake phobias] because they’re weirdly given agency. They’re not flat characters.”

Geography is an important character, too. Set in Denver and the Lost Territories, making up what is now referred to as northwest Arizona and Southern Colorado, Woman of Light is deeply rooted in place. If readers are at all familiar with the history and topography of the Southwestern region—especially Denver—they’ll find themselves filled with delight when they see towns and names mentioned like Five Points, Lookout Mountain, Colfax Avenue and Aminas.

In all Fajardo-Anstine’s stories, the Colorado she presents is incredibly diverse, consistent with her own background as a Latinx and Indigenous woman with Filipino and Jewish roots. But it’s also the only version of Denver she’s ever known. “I had neighbors from Nigeria, a large Navajo family next door, a well-known Chicano muralist and his activist wife on the other block,” says Fajardo-Anstine. “Many of my friends in middle school and high school were from Hmong and Chicanx backgrounds and many mixed people. I grew up as an Azteca danzante (dancer) and our world was always very rich with community, service and tradition.”

But Woman of Light is not merely a novel set in the Southwest. It centers the communities that Colorado and other western states like it have long attempted to erase and ignore. That Fajardo-Anstine writes Western literature is undeniable. She completely shatters the expectations that have been set around the genre—namely that it be white and male, often dehumanizing to Indigenous people, and featuring reductive portrayals of the land and animals of the Southwest.

When she was getting her MFA in creative writing at the University of Wyoming, Fajardo-Anstine says she noticed that white Western authors were at the forefront, and people like her were erased. “Their voices were louder than mine,” she recalls. “They were being published in big magazines. I made a conscious decision that I needed to include my voice. I needed to make it my life’s work to make sure that my perspective and perspective of people like my family were visible in this narrative space.”

The vision for Woman of Light came even before that. It has been an ongoing project for 10 years. Fajardo-Anstine first got the idea in her late teens, when she worked at West Side Books in North Denver, surrounded by Western novels that didn’t feature people like her and her family. “I was really frustrated that people like my family, my ancestors, we didn’t have any novels that we could look at and see ourselves.” She has also been inspired by others trying to boost representation in this space of Indigenous Western American literature, like Stephen Graham Jones, Chelsea T Hicks, Tommy Pico, Kelli Jo Ford, Brandon Hobson, Oscar Hokeah and the musician Christian Wallowing Bull.

At its core, Woman of Light is, in many ways, a gift to Fajardo-Anstine’s family. A mirror, pages of immortality that will live on because their stories have been written.

“My godmother who’s in her eighties—she’s my Auntie Lucy’s daughter, so she’s also my cousin—told me when she was reading it, she said aloud to my uncle, ‘Look, you’re in this book,’ and she cried. She said that she is so proud that people are going to know about us.”