The existence of Black women artists in Southern-shaped music genres didn’t begin with Beyoncé, but at present, the Texas-bred icon is revolutionizing the movement in an act (II) of courage.

The country twang and defiance of Beyoncé’s latest singles “Texas Hold ‘Em” and “16 Carriages” venerate the legacies of progenitors: The gun-toting Mississippi blueswoman Jessie Mae Hemphill and angelic South Carolina yodeler Linda Martell; The rich vocalizations of Leola Manning and Bessie Smith, without whom there would be no meaning to Appalachian music, the regional sound that popularized the banjo; The folk-laced greats like Smith’s “Washerwoman’s Blues” and 1928 Hattie Burleson’s “Sadie’s Servant Room Blues” that were rife with messages of protest and created fellowship among Black women.

When Cowboy Carter, Beyoncé’s eighth studio album, releases on March 29, this movement will unlock a new level of visibility in country music, an opportunity Black modern country and Americana artists are rightly capitalizing on. It’s her first full-length romp into these genres, largely defining her Houston origins—but this isn’t Beyoncé’s first rodeo. Her country tease began with “Daddy Lessons,” a song so defiant to her discography that it shook up the 2016 CMA Awards and got its own chapter in the 2022 Francesca Royster-penned book, Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions. And while Beyoncé insists Cowboy Carter is a “Beyoncé album” rather than a country album, fans are still ready for her to gallop into the country arena with more Southern-inspired records and illuminate other Black women in the genre.

“For us, if you really listen to these songs and the stories that are being told, it’s like, ‘Wait, this is the stuff that we know,” artist Devynn Hart tells Sweet July. “This is how we grew up. This is the life that we live.’” Hart covered “Daddy’s Lessons” earlier this year and embraces country music among a small population of Black residents in Poplarville, Mississippi. “Naturally, that’s what gravitated us towards country, just being able to relate on a different level.”

Hart, who cut her teeth into primetime recognition as part of the Chapel Hart singing group in season 17 of America’s Got Talent, is now curious about the sudden notice of Black country artists and if it will persist after Cowboy Carter. “I am interested to see how it plays out, because right now it’s the trend to follow, but will the trend continue?” she says. “Will people continue looking for Black artists and different artists in country? I hope that it isn’t just a trend, and then later on, after a few weeks, it’s like, ‘Alright, now what’s next?”

But Americana singer-songwriter Denitia acknowledges that before the Cowboy Carter announcement, Black artists in the Nashville scene were already having conversations about widening their reach. “It’s like, man, how do we get to Black audiences?” says Denitia. “Because we know that there are people who love what we do, we’ve just got to get to them.”

Transitioning into Americana—a Southern-based genre that incorporates American roots music—was seamless for Denitia, who grew up in Dayton, Texas, just on the fringes of Houston, attended college in Nashville, and has roots in Louisiana. After a post-grad move to Brooklyn and becoming one-half of former electronic pop duo Denitia & Sene, Denitia honored her hometown roots on her 2022 LP, Highways. The album, which she says “grounded” her, preceded a relocation to Nashville last year.

Denitia isn’t shy about speaking to the visibility problem Black women in country music are facing—even Beyoncé, whose latest singles struggled to reach the country radio rotation in its early release days. Despite these shut-out efforts, in February, “Texas ‘Hold Em” debuted atop Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart, later going No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, making Beyoncé the first Black woman to achieve both feats with a country track. The breakthrough is unsurprising to many, including Denitia.

“There was a lot of pressure for [radio stations] to make a different decision,” says Denitia. “I think part of the power of this moment is some of the resistance and seeing some of that resistance fall away.”

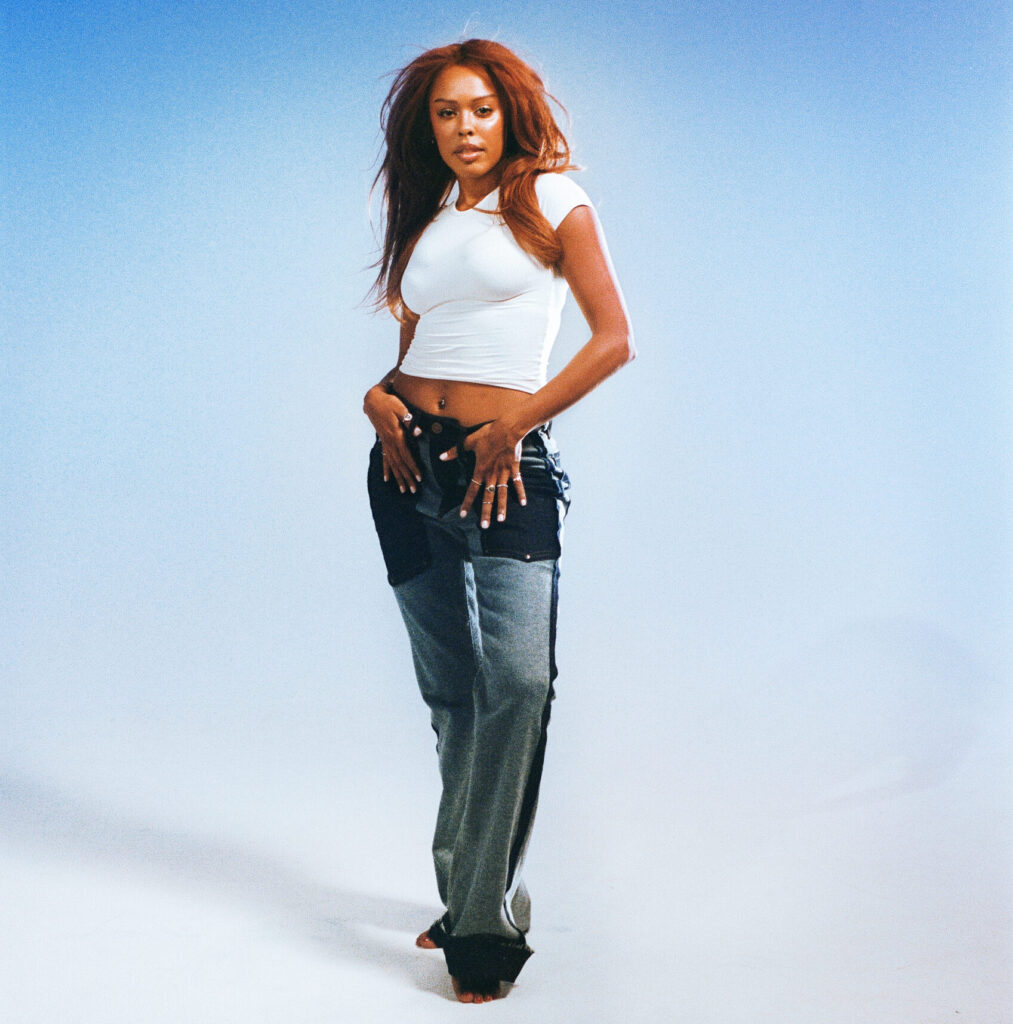

Playing a major role in the watershed of disruption in country music is Nashville-based act Reyna Roberts, whose fiery scarlet locks are equally daring to her ‘Bad Girl’ persona. From a military family, Roberts, who was born in Alaska, lived in several states before making her breakout in Music City with her 2020 single “Stompin’ Grounds.”

“If radio stations were hesitant to play Beyoncé or didn’t want to, how difficult do you think it’s been for people like me, Brittney Spencer, Mickey Guyton and a lot of other people of color in country music?” says Roberts. “That just gives people a perspective on what we’ve been trying to go up against in terms of being played on radio.”

Her perception is reality; a study from musicologist Dr. Jada Watson, titled ‘Redlining in Country Music,’ shows that in 2020, less than 0.01 percent of Black women were played on country radio. But disproportionately overlooked performers strive to beat the odds. Receiving an early co-sign from Mickey Guyton, the first Black woman to be nominated in the Grammy category for Best Country Solo Performance (an appropriate gesture for her protest single “Black Like Me”), Roberts sits firmly among these current Black country music disruptors.

“If you listen to me or Tanner Adell or Brittney Spencer, Mickey Guyton, etcetera, we’re all so different in this space and I love that,” Roberts adds. “We are bringing people into country music [who] might not listen to country music. That makes me grateful.”

For others, like North Carolina-raised ‘southern pop’ singer Camille Parker, the main goal is maintaining reverence for country music’s yore while maintaining her individuality, no matter the reception from listeners. The artist recently made her Grand Ole Opry debut, where she was able to reintroduce her “full self” to a crowd that seldom witnesses Black artists take on the premier Nashville stage.

“I’m not trying to win the countriest country girl competition,” says Parker. “I’m just here to be myself and make a sound that still fits on your playlist. If you’ve seen somebody with a little twang in their voice that you like, and you kind of like that storytelling, but you also listen to SZA and Beyoncé, I’m the girl for you.”

Tampa native and country-Americana artist Julie Williams nearly left the industry due to its influence under white men with patriarchal and conservative views. “Southern Curls,” a song from her 2023 eponymous EP, even garnered an offensive reaction during an event from a male music publisher who didn’t understand its message. Williams had the diverse textured hair of Black women in mind when she wrote “Southern Curls,” but the publisher suggested that she change the title to “Southern Girls” for the sake of racial equality.

“To have someone say, ‘Oh, I think the song is great, but the story behind it needs to change’ was one of the first times when I was like, ‘Oh, wow. This is not going to be the easiest road if I want to do the songs that I want to do in this genre,’” says Williams.

Instead of entertaining microaggressions, Williams simply turns her attention to the community that she’s built in the South, a sacred train of Black country descendants cherishing the mainstream launchpad Beyoncé has set. A zeitgeist of reevolution, Beyoncé’s giving us another round of the #YeeHawAgenda and uplifting other Black female country performers, both past and contemporary, as if it were her intention all along.

“Whether they’re listening to Beyoncé’s music or they find their way onto the catalogs of folks like myself, I hope that they see themselves,” Williams adds. “If you suddenly discovered this music and you find yourself drawn to it, I say, ‘Come on in, welcome to the party.’”